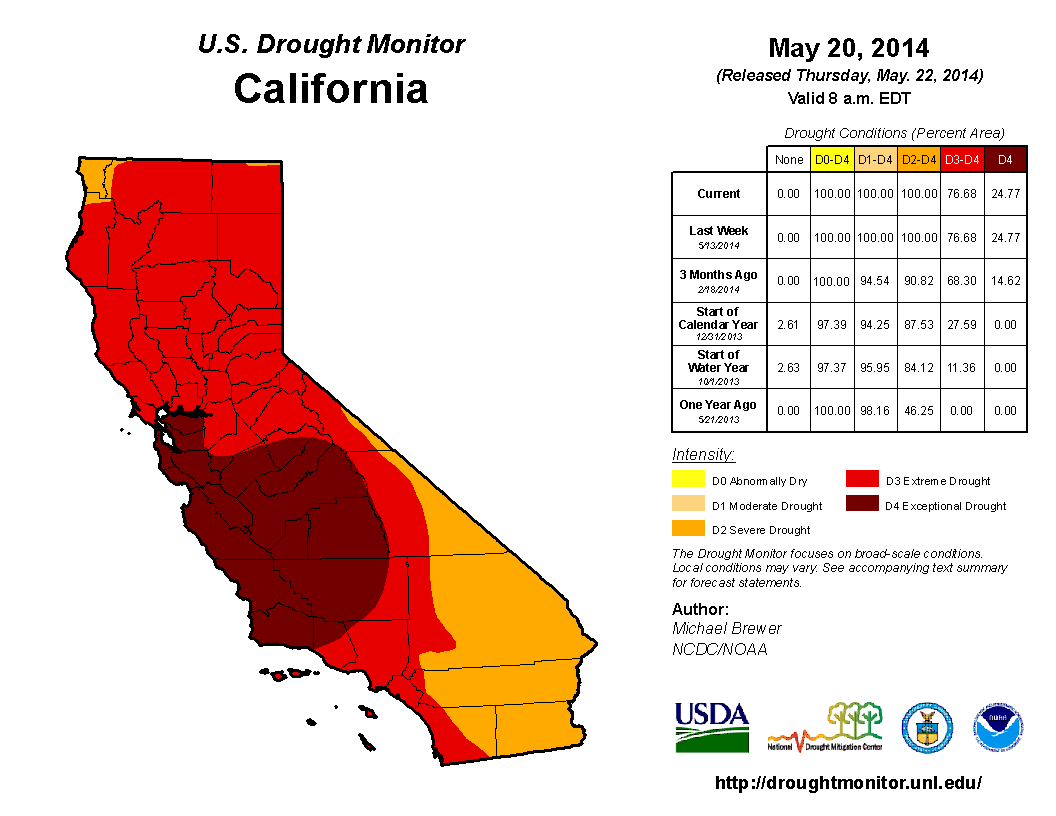

The year 2014 is exceptional for California weather, and has the potential to be a similarly exceptional year for wildfire. All of California’s 58 counties are in a drought, with greater than 20% of the state in extreme drought since February 2014[1]. From October 2013 to April 2014 only 51% of average precipitation fell in California, and snowpack as of May 23rd was at 5% of normal[2],[3],[4]. Since December of 2011, greater than 60% of the state has been classified as abnormally dry[5]; that percent was surpassed and has remained above 95% since March 2013[5].

California’s drought is just part of the story—heat is another. Winter of 2014 was one of the warmest on record throughout the state. The months between January and April 2014 were 3 to 6°F warmer than long-term averages[6], and maximum temperature records were repeatedly broken3. Early Santa Ana winds brought low humidity, record high temperatures[7], and severe fire weather to Southern California in May, where eight simultaneously occurring fires burned over 29,308 acres[8].

Long-term drought, high temperatures, and winds are a deadly combination in a state historically impacted by wildfire. Consistent dry and warm conditions caused the 2013 fire season, which began in mid-April 2013, to blur into 2014. With summer rapidly approaching, no relief is likely until winter. Already in 2014, 1,563 fires have burned, nearly double the five-year average for the state[9],[10], and the fire season has yet to reach its stride: the twenty largest wildfires in California history occurred between the months of June and October[11].

The extended drought conditions after three dry winters in a row has created dry fuels and increased fire risk. Because of past fire suppression policy, fuels have accumulated[12] in California’s forests, primarily in those that once experienced frequent, low-moderate intensity fires. It is estimated that less than 20% of national forest and park lands are receiving needed fuel treatments[13]. A great management need is to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration projects in the state. Standing dry fuels, when combined with fire-friendly weather conditions, lead to favorable conditions for catastrophic wildfires, a huge and expensive threat to people and landscapes. Chaparral shrub fuels are particularly hazardous in the southern part of the state that has the largest urban-wildland interface.

prescribed fire

Wildfires are costly, for government, communities and the environment. In 2013, 9,907 wildfires burned 577,675 acres in California[14]. Nationally, in the same year 67,774 fires burned 9,236,238 acres, bringing federal fire suppression costs to $1,740,934,000[15]. In 2014, Cal Fire went to peak staffing two weeks earlier than in 2013, reaching a state total of 5,000 firefighters and $600 million appropriated dollars for wildfires[16].

Though this year is certainly unusual, wildfire is a condition Californians will never be free of. Climate change will likely continue to bring increased temperatures and earlier snowmelt, yielding increased fire frequency and fire size, and suppression will continue to be unable to keep up with the growing number of destructive fires[17]. There are many steps California residents (and others concerned about wildfire in their communities) can take to reduce the threat of wildfire, including using fire-safe housing and landscaping practices, being safe when using fire outdoors, and more.

For additional resources, visit:

- http://ucanr.edu/sites/cfro/Resources/

- http://www.preventwildfireca.org/

- http://www.fire.ca.gov/

- http://www.readyforwildfire.org/

- http://www.nifc.gov/

- http://www.firewise.org/

- http://www.nfpa.org/

- http://inciweb.nwcg.gov/

- http://www.esri.com/services/disaster-response/wildlandfire/latest-news-map

Authors: Carlin Starrs, Policy Analyst, UC Berkeley Center for Fire Research & Outreach[a]

Scott Stephens, Co-Director, UC Berkeley Center for Fire Research & Outreach[b]

To receive regular updates like these from the UC Center for Fire Research and Outreach in your inbox, sign up for our mailing list.

[1] http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/Home/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?CA

[2] http://cdec.water.ca.gov/cdecapp/snowapp/sweq.action

[3] http://www.wunderground.com/blog/JeffMasters/comment.html?entrynum=2680

[4] http://e360.yale.edu/slideshow/nasa_images_show_severity_of_californias_record-setting_drought/263/1/

[5] http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/MapsAndData/DataTables.aspx?CA

[6] http://www.water.ca.gov/floodmgmt/hafoo/csc/climate_data/

[7] http://mashable.com/2014/05/14/california-wildfires-santa-ana-winds/

[8] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_2014_San_Diego_County_wildfires

[9] http://cdfdata.fire.ca.gov/incidents/incidents_stats?year=2014 (as of May 17, 2014)

[10] http://www.weather.com/safety/wildfires/california-fire-season-year-round-20140514

[11] http://www.fire.ca.gov/communications/downloads/fact_sheets/20LACRES.pdf

[12] http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu/pdf/8245.pdf

[13] http://static.squarespace.com/static/50083efce4b0c6fedbca9def/t/52fe7448e4b0c3ca59bdbae3/1392407624273/North_etal_2012_Feb-2014.pdf

[14] http://www.predictiveservices.nifc.gov/intelligence/2013_Statssumm/fires_acres13.pdf

[15] http://www.nifc.gov/fireInfo/fireInfo_documents/SuppCosts.pdf

[16] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/05/18/jerry-brown-california-wildfires-_n_5348103.html